On 10 February, the Sign Design Society made its twice postponed visit to the Abram Games archive. This visit was significant because it’s the first in-person event the society has organised since the start of the pandemic in 2020. Little did we know the absolute wealth of treasure awaiting us. We were a small group of six making the visit. I worried that Naomi Games – Abram’s daughter and the custodian of the archive – might be rather underwhelmed by the small size of the group. In fact, it was ideal as we cosily sat around Naomi’s kitchen table to view the artwork.

On 10 February, the Sign Design Society made its twice postponed visit to the Abram Games archive. This visit was significant because it’s the first in-person event the society has organised since the start of the pandemic in 2020. Little did we know the absolute wealth of treasure awaiting us. We were a small group of six making the visit. I worried that Naomi Games – Abram’s daughter and the custodian of the archive – might be rather underwhelmed by the small size of the group. In fact, it was ideal as we cosily sat around Naomi’s kitchen table to view the artwork.

The archive is currently housed in Naomi’s home while she searches for a more suitable, publicly accessible location. Her north London flat is not only home to her father’s archive but also for a creative and imaginative family, as attested by the variety of artwork displayed on the walls.

Naomi started our visit by demonstrating the Cona coffee machine her father designed. It was intriguing to see the simple mechanism working. It made delicious coffee as she explained how her father was so much more than the famous designer that we know. He was a prolific inventor who was forever seeing ways of improving the products around him.

We also saw Abram’s much-used airbrushes. This was our first glimpse of the now-forgotten handcraft skills that were essential for graphic designers in the mid-twentieth century.

Naomi then took us into her kitchen, where a large pile of plastic sleeves lay on the wooden table. She informed us that this was no more than the tip of the iceberg. It was a small part of the archive that fills all available spaces in the flat, and occupies storage units elsewhere. Naomi explained that she is hoping to find a more suitable home for the archive. One where it will be accessible to students and the general public, not locked away in an academic archive repository.

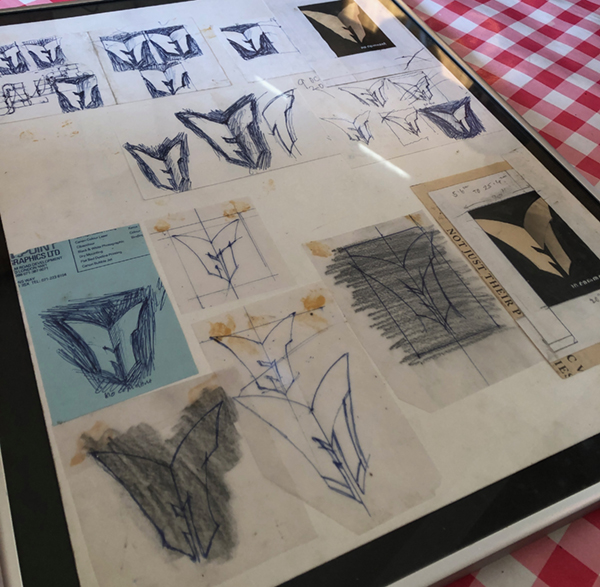

Naomi emptied file after file of sketches, working drawings, presentations, and production artwork on to the table. Abram Games had kept most of his working drawings. And he had numbered them. It is possible to watch in meticulous detail as an idea takes shape and becomes the finished item.

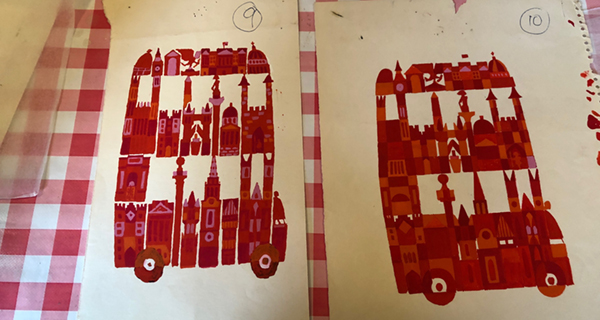

A favourite example was a poster advertising sightseeing on a London bus. There are upwards of fifteen stages of development. They show how the idea started as a montage of London landmarks and gradually morphed into a bus made up of the landmarks. It was almost as if we could hear Abram Games’ inner dialogue in the design process: ‘what if I try making the landmarks a bit closer … what if I try taking out the gaps between them … oh, if I add wheels it looks like a London bus … does it look better with or without black outlines … can I make the windows a bit more regular … how does the lettering fit in …’ and so on. This work was all executed on paper or card rather than the computer screen which is the site of most design activity these days. (Note to modern designers: do you keep evidence of the iterative creative process? If you do, how will you access those files when you no longer have the applications that created them?)

We saw so many of his design projects grow from initial pencil ideas to finished colour artwork before our eyes. We saw plentiful poster designs for all sorts of clients, including many for the Financial Times. And we also saw all sorts of other graphic products, such as a wide range of symbols and logos, book covers, and many postage stamps. All these gave views into Abram’s working processes. His long career meant that we could see his style evolve as fashions changed. We also saw the childhood drawings of Naomi and her siblings. They appeared on Abram’s working drawings, presumably keeping his children entertained as he worked at home. And we saw Naomi collaborating with her father in some of his later work, when she was a trained designer with a career of her own.

For a generation who have grown up designing on computer, it was also an education in the hand crafts that used to be an essential part of design. We saw Abram’s virtuoso use of the airbrush. As well as his mastery of sketching in pencil, ink, biro, and paint, and impeccably finished presentation work in gouache. And we saw the traces of now forgotten, once commonly used products such as Cow Gum (oh, remember those heady fumes!), rouge paper, and Kodatrace.

One fascinating insight was Abram’s practice of producing poster visuals at thumbnail size. Tiny little jewels of work. While it might seem a bit strange to make such a tiny visual of such a large item, actually it’s a good way of assessing whether a design will be intelligible when viewed fleetingly from a distance.

The pile of files that Naomi had selected from the extensive archive turned out to be an extraordinary treasure trove. It demonstrated the breadth of Abram Games’ work and his mastery of so many genres.

As a practising designer, it was a privilege to have such an insight into the working methods of one of the UK’s greatest 20th-century designers. And delivered by his daughter Naomi, we gained a much more complete picture of the man as a person in the context of his own family. It made Abram Games less of a remote, iconic figure from design history when the person presenting the archive kept referring to him as ‘Daddy’.

If you ever get an opportunity to visit the Abram Games archive, go and see it – you’ll definitely be inspired.

Any questions, or like to arrange a tour? Get in touch with Naomi Games at: enquiries@abramgames.com.